By 2030, the European Union aims to boost the proportion of freight transported by rail to 30 percent, from just 18 percent today. The industry believes that digitizing and automating freight cars equipped with the Digital Automatic Coupler (DAC) is the best way to achieve this – but the transition is fraught with challenges.

At present, wherever freight trains are assembled in Europe, the process looks like something out of a history book. Shunting marshals stand between freight cars, wrestling to connect screw couplings and brake lines. And other preparatory steps are still performed manually – such as the mandatory brake test. Here, marshaling staff walk down the entire length of the train on one side, then back up the train on the other, checking each brake individually. At the same time, their colleagues are checking loading doors or mounting end-of-train devices as required. This process has remained essentially unchanged for the last 130 years, which is why it can often take hours to prepare a freight train for departure.

Contact

80809 München

Deutschland - Germany

carina.smid@knorr-bremse.com

Too slow, too cumbersome, too complicated: Why rail freight needs a relaunch

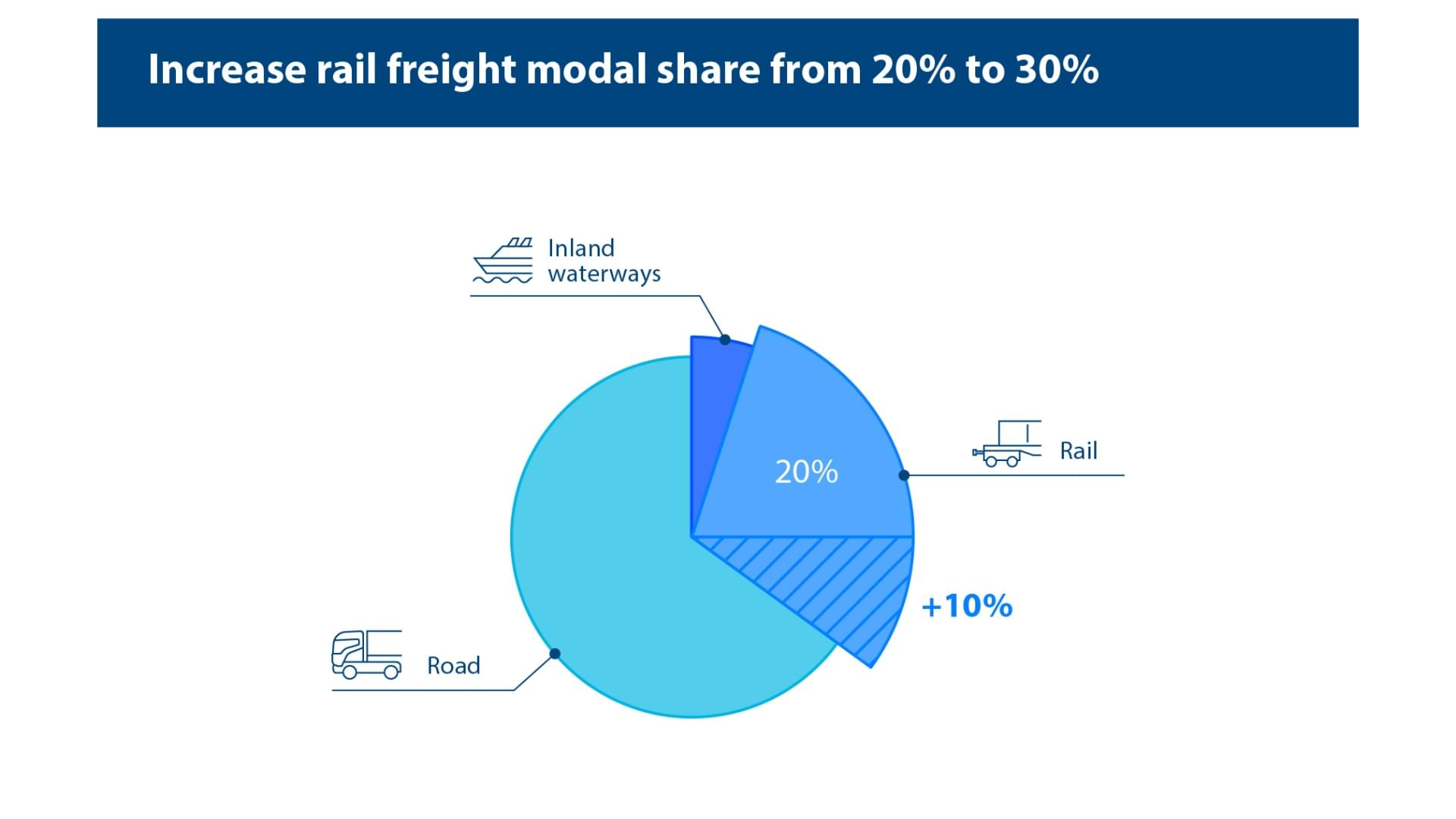

The European Union (EU) has set ambitious goals for the future of rail freight. By 2030, it wants to boost the volume of freight transported by rail up to 30 percent from the current level of just 18 percent [Fig. 1]. That the EU should take this transition so seriously is scarcely surprising: Per tonne-kilometer, a freight train only emits some 17 grams of CO2 – a truck, on the other hand, emits 111 grams [1]. And apart from rail, no other mode of transportation is capable of transforming itself so rapidly to run entirely on renewable energy, using electricity generated from renewable sources.

However, based on today’s rail freight practices, this 30-percent goal will remain unattainable. The many manual processes involved in preparing, assembling and operating freight trains are a major reason why the rail freight sector finds it so difficult to compete with road freight. Given the amount of time it takes to assemble freight trains, single-car routing in particular no longer meets twenty-first century requirements for flexible supply chains. To keep up, the rail freight industry needs a relaunch, in the form of end-to-end digitization and automation.

Smart, automated processes need smart, automated vehicles – with the DAC as a key enabler

The Digital Freight Train (DFT) could be the catalyst for this transformative relaunch. Starting with individual freight cars – of which some 500,000 are currently in use across Europe as a whole – automated processes and digital solutions are expected to boost transportation capacity, efficiency and availability. The end-result would be smart, intermodal fleet operations, in which individual freight orders would appear to find the fastest route to their destinations as if by magic. But using smart, automated processes to operate everything from individual freight cars to entire train fleets presupposes smart, automation-compatible vehicles (freight cars and locomotives).

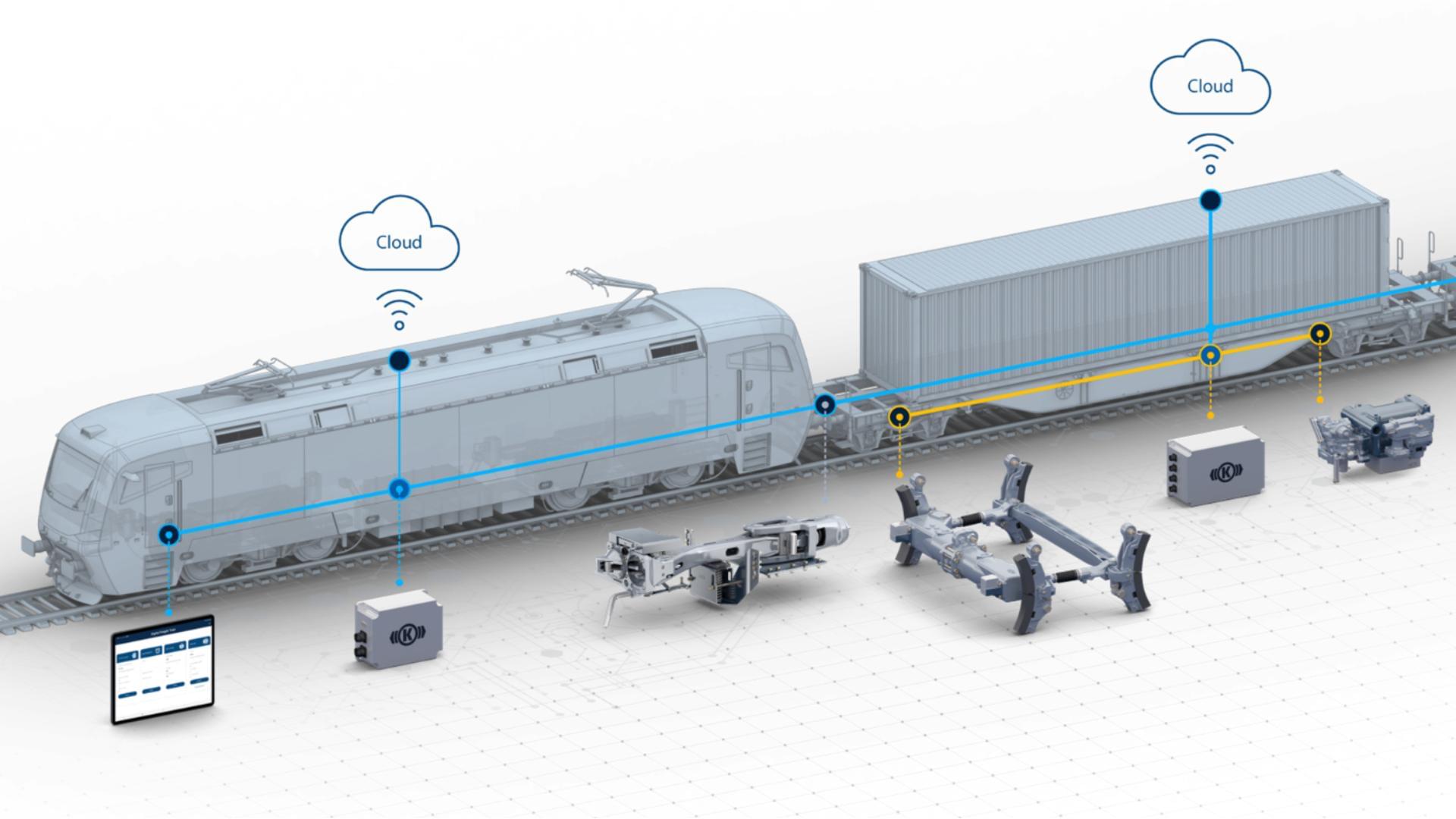

In turn, smart, automation-compatible vehicles need digital automatic couplers (DAC). Long standard in the passenger sector, this function would, first, simplify the labor-intensive manual coupling process by automatically establishing the necessary mechanical and pneumatic connections between freight cars (and the locomotive). And second, it would automatically connect the locomotive’s electronics and energy supply to the railcars, establishing a communications network along the entire length of the train and linking it to the rail operator’s cloud server. Equipped with “electronic intelligence” in the form of control systems, sensors and actuators, the coupler would be capable of acting as the key enabler for almost all future digitization and automation functions ever required by the rail freight industry.

The most obvious and significant changes would affect the manual train preparation processes mentioned at the start. Automated brake testing would hugely improve efficiency in the shunting yard by making the time-consuming, on-foot inspection of the trainset obsolete. And remote control of the coupler would – as the name suggests – make it possible to remotely decouple a trainset. The DAC also supports direct control of the parking brake that prevents vehicles from accidentally rolling away. A fully equipped DFT would also transform train setup and train integrity monitoring into automated features that would be easy to implement [Fig. 2].

But above and beyond these functions, the DAC has even greater potential. Provided that the operational benefits justify the additional cost, the DAC could also pave the way for the introduction of an electropneumatic braking function specifically designed for freight trains, because the DFT would already be equipped with the basic prerequisite for this: an electronic infrastructure. And in any cost-benefit analysis of a digitized rail sector, further DAC-related benefits appear – it could also serve as a platform for condition-based maintenance (CBM) applications.

Consistent standards across the entire European rail freight market

Given the importance of interoperability across Europe’s member states, the DFT’s attractive added value should not be allowed to obscure the complexity of the technological developments required, or of the subsequent market rollout. Like the UIC regulations and EU standards that have evolved for pneumatic braking systems, a similar set of rules and standards is urgently required to put the DFT into operation. Ultimately, the importance of long-term interface compatibility should not be allowed to hinder the ongoing technical development of the system as a whole.

Under the aegis of the EU technology support program “Europe’s Rail Joint Undertaking” (ERJU), Europe’s vehicle manufacturers, rail operators and supply industry continue to negotiate safety and availability targets that are as generic as possible. However, the actual safety certificates used for the approval of DFT freight cars and locomotives must be directly relevant to and valid for the individual vehicles concerned. The new technology must also be integrated into the latest maintenance concepts: Ultimately, it should be possible for any workshop in Europe to service or repair any DFT-compatible vehicle.

A look back into the recent past is enough to show just how urgent the 2030 goal mentioned at the start of this article has become: While the mere act of standardizing the DAC’s mechanical interfaces might seem comparatively straightforward, in reality the European rail vehicle industry spent years finalizing these standards.

Author: Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Steffen Jass

Literature:

[1] Höhe der Treibhausgas-Emissionen im deutschen Güterverkehr nach Verkehrsträgern im Jahr 2019. Statista